In the wake of the Chicago Cubs’ failed pursuit of Alex Bregman, the signing of Justin Turner to a one-year deal was largely viewed as a positive. Despite some declining elements of his game, a veteran hitter committed to the craft looked to be a quality addition to a group in need of some supplementation off the bench.

“Despite” is doing a lot of work in the previous sentence, however. And while there are certainly some unquantifiable components that he brings to what has been one of the league’s most successful offenses, those initial concerns we had around Turner are manifesting at their maximum—which, obviously, isn’t a good thing.

Turner’s slash on the year includes a mere .170 batting average. He’s reaching base at just a .270 clip, even with a reasonable 11.1% walk rate. It’s not like the skill set is entirely diminished within that. Particularly from a cerebral standpoint. Turner’s approach remains ever-solid, with chase and contact rates that are fairly in line with what he’s turned in over the past handful of seasons. From a pure discipline standpoint, he’s been exactly as advertised.

But one of the main caveats with signing Turner was that you weren’t getting the actual hitter that he’d been in years past. That’s not a shocking statement, given that you’re talking about a 40-year-old hitter. Bat speed falls off a cliff in one’s late 30s. There are ways to work around that. In Turner’s case, though, it’s become a real issue. While a high volume of impact wasn’t necessarily expected, the Cubs are getting no impact out of their veteran infielder.

The eye test alone could tell you that, but the numbers do, too:

Nor is it any kind of mystery. Turner’s bat speed is in its third (well, probably more than that, but we only have data for three) consecutive year of decline, to the point where it’s the seventh-slowest of hitters with at least 50 swings on their ledger. His rate of fast swings (classified as any swing over 75 MPH) is a literal 0.0%. To see that lack of hard contact depicted above continue its decline is just verification of what anyone who has watched him swing a bat this year already knew to be true.

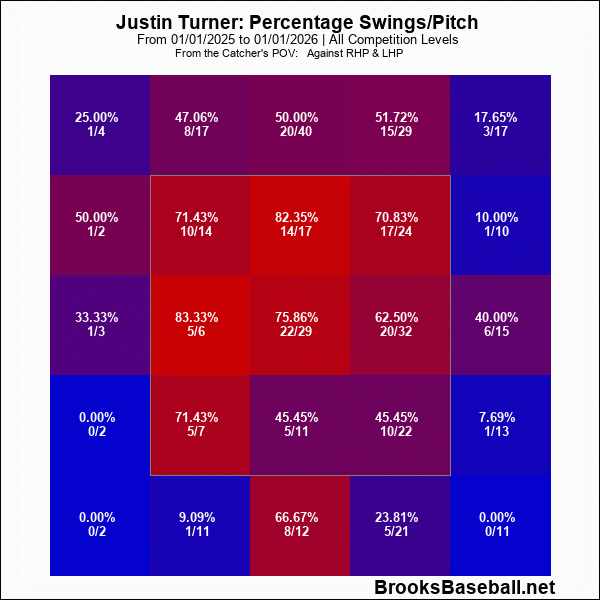

Making matters worse is how much of that contact is on the ground. Exactly half of Turner’s balls in play are of the groundball variety. That both is and is not surprising. On one hand, Turner isn’t swinging in the portions of the zone designed to general groundball contact:

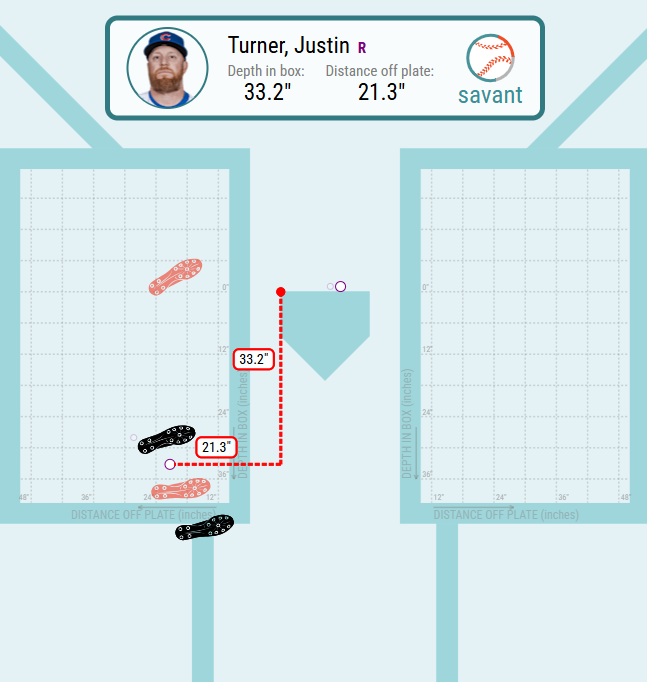

But on the other, he’s just late. He’s a catch-it-out-front guy, but in just under two years, he’s gone from hitting it 39 inches from his own center of mass to making contact at 34 inches. A deeper contact point is a bad sign, for the guy who made “gaining ground on the pitch” a famous mindset in the modern game.

It’s all wrought by Turner’s poor bat speed. That the approach and contact trends remain in his favor provides some value, I suppose. But when you’re generating virtually nothing when the ball winds up in play, a real problem presents itself.

The Cubs signed Turner not just to contribute off the bench, but to shield Michael Busch (and, more indirectly, guys like Gage Workman or Nicky Lopez) from facing lefties. As good as Busch has looked, he still has just 19 plate appearances against southpaws. Turner’s been the only alternative they’ve really explored, despite a wRC+ of just 53 against lefties.

No immediate solution has presented itself in Turner’s stead. He’s going to remain on this roster, as long as there’s an absence of approach-oriented veteran hitters available. The money the team spent on him helps ensure that, but since neither Workman nor Matt Shaw proved able to do anything useful early on, there’s also no one around you’d rather have take those chances. Nor is anyone in a hurry to push the beloved Turner out through the back clubhouse door. But aside from whatever intangible qualities he’s providing, there simply is not a lot he does for the roster at present. It’s a problem. But unlike the Cubs’ marquee veteran with already-alarming peripherals on the mound, it’s one without an immediate solution.